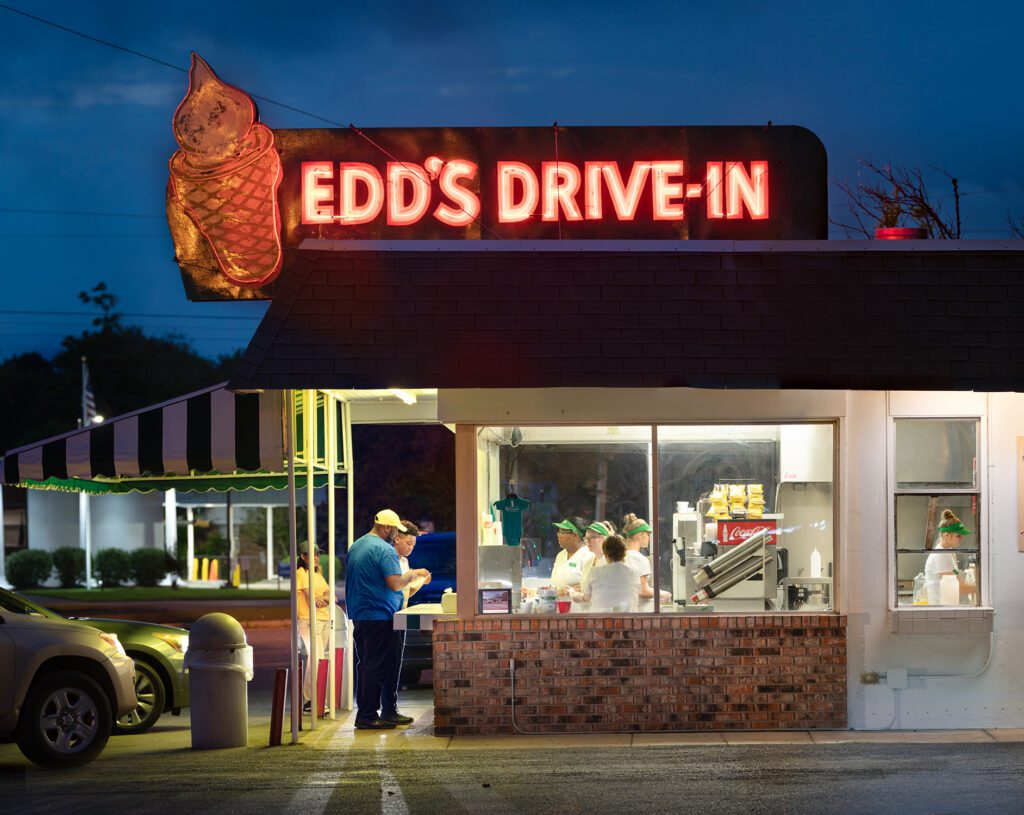

Colored Window at Edd’s Drive-In, Pascagoula, MS ©Richard Frishman

Richard Frishman received a Fellowship in Photography in 2021 to work on his project, “Ghosts of Segregation.” During his Fellowship year, Frishman road-tripped all around the United States, taking photographs of places that still carry traces of our country’s history of racist policies and actions. The photographs became a book of the same title, which was released in February. Frishman worked with the ethnographer B. Brian Foster on essays to accompany the images, and the book’s foreword was written by Imani Perry, a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow in Intellectual and Cultural History, National Book Award-winning author, and MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient. Last month, just after the book’s release, we spoke to Frishman while he was at home in Washington State.

Guggenheim Foundation: Your book just came out a few days ago. How has this week been?

Richard Frishman: It’s rewarding. It’s a little unnerving to suddenly be getting so much attention. Personally, I want the attention to be about the project, because that’s what really matters. I feel like the project is painfully important. Unfortunately important. I wish that we were in a different place as a society, where we were fully conscious and appreciative of our many connections. That’s part of why I pursued this project. I want to provide opportunity for conversation, and encourage curiosity about the environment that surrounds all of us. Wherever we may be. Anyhow, it’s been a great week and I hope that the book is well received and accomplishes some of my lofty (and perhaps naive) goals.

GF: I’d love to hear more about how you found your way to photography to begin with.

RF: When I was just a kid, my family moved to a neighborhood outside of Chicago where there weren’t any kids around for me to play with. And my grandfather—my Grandpa Izzy—gave me a box camera for my fifth birthday. I used that as substitute for playmates. I would photograph all around our house. I particularly focused upon my sister, and then my brother once he was born. I think I tormented them with that camera, but it gave me so much pleasure to see the world on little pieces of paper and realize that I could record moments and preserve them. I just took to it and never stopped. It’s like it opened a door to my destiny.

I’m doing what I was meant to do—I found my purpose and really pursued that with a passion. I’m 72, almost 73 years old. So, for 67 years, I’ve been doing this. I had other aspirations at different times. When I went off to college, I anticipated being either a lawyer or a doctor because I loved science and I loved the idea of equality and justice. That was a very fundamental aspect of my childhood: my parents were very socially conscious. When I was old enough to start looking at Life Magazine, I became particularly enamored with photojournalism. But I didn’t have any role models of photographers. I had role models of doctors and attorneys. My dad, though, was a builder and he loved architecture.

GF: How did that factor into your future work?

RF: My dad was an unrequited architect. He had wanted to be an architect, but his family’s finances precluded his finishing his college education. He became a draftsman and, later, a general contractor. But his love of architecture, his interest in people; he passed those down to me. I remember every day I had off from school, he would take me down to Chicago, either to the Art Institute, or to see a musical at the Schubert Theatre. In the morning, before those events would happen, we’d stop at some of his work sites, and he would tell me about the buildings and the architecture that we passed. Mies van der Rohe had some stunning new buildings; my dad would wax rhapsodic about their beauty—all the glass and the steel. He would take me by places that were either being torn down, like the old Federal Courthouse, or places that were saved by preservationists, like Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Theatre. He just loved Sullivan.

I can’t say that, at 8 or 10 years of age, I fully appreciated what I was being taught, but at some point it clicked that the buildings and places and our built environment itself, our roadways and the way cities are laid out, all have stories to tell us; stories from which we can learn.

For most of my life I have focused my lens on people and the human condition. In the last decade or two, I started looking at place as an embodiment of people and history. In a lot of my photographs of people, there was an emotional intensity and a visceral quality that could be quite off-putting, more than one would want to meditate upon. That’s not so true when I photograph places. Those are more emotionally digestible, less visually violent. They are more thoughtful and descriptive, rather than visually traumatic and prescriptive.

GF: If you’re taking photos of people in particularly devastating or heightened emotional situations, I think that a subject’s face tells the viewer how to feel. Whereas with these images of place, that are more subtle, there’s perhaps more of a conversation between the art and the viewer, where the viewer may have to work a bit harder to understand what the emotional impact should be.

RF: You distilled that very well. I think that’s exactly right.

GF: Could you tell me about your Guggenheim Project and how it began?

RF: Sure. My background in photojournalism had me on location, shooting for Sports Illustrated, LIFE, Forbes, and Businessweek. I was photographing athletes and financially successful people, two realms I know little about. I was always interested in the little towns where I would land, so I started photographing aspects of these communities in my free time. That led me to consider how I could give voice to the history that is embedded around us and what it says about our culture. All human landscapes have cultural significance. Because if we don’t think of our constructions as revealing much about us, we don’t bother to edit. If you asked me about Rich Frishman, I would give you an honest but edited answer: I’d highlight the stuff that I’m proud of, and I would hide the stuff I’m ashamed about. I came to the conclusion that the vernacular landscape is an authentic and honest autobiography of our society.

Before the “Ghosts of Segregation” project, I was engaged in photographing a more upbeat history of America, focused upon mimetic architecture, roadside curiosities and materialism. That suited me for a number of years; it allowed me to express my sense of irony and humor. By mid-2016 I began feeling that there were more important issues that needed to be addressed: inequalities, prejudices, and the rising tide of racism washing over America. Visual evidence of racial and ethnic animus, both contemporary and historic, is embedded in our landscape.

When I was a child, the modern civil rights movement was just coming into our collective awareness. More specifically, our white collective consciousness. Black people had to live with the struggle 24/7 just to survive.

I was born in 1951. One of my earliest memories, before I could read, was coming into the kitchen one morning and seeing my mom sitting at the kitchen table, crying, with a cigarette in her hand and the newspaper open. I was frightened by her sadness and wanted to comfort her. She tried to explain about a child who had been killed. Mom was talking about Emmett Till. He was from Chicago, too, and about 10 years older than me. My parents were very progressive and open-minded.

Their own parents had fled Europe to escape antisemitism. My great-grandfather had been killed in a pogrom. They taught us to appreciate what was inside people, not the outside. When there would be news—like Emmett Till’s death—it would become an opportunity for an object lesson in equality. How to appreciate that people might look different, but that we’re all humans. I didn’t know anything about what it was like to be Black—I still don’t—but I learned to be curious and concerned and compassionate.

By the mid-2010s I was aware that the demons, which I had naively thought were departing, were being nurtured and invited back into our shared house. I felt the need to raise my voice in alarm and opposition. As a photographer, the best thing I can do is open peoples’ eyes. I started researching and photographing places that were historic in terms of the civil rights struggle; the vestiges of racism that surround us.

As a photographer, the best thing I can do is open peoples’ eyes.

GF: Can you tell me about the first photograph that kicked off the “Ghosts of Segregation” project?

RF: Yes. I can even tell you the date. It was March 20th, 2016. I was still doing my more sanguine exploration of how history is represented in our built environment. I was in Gonzales, Texas, a historic town where the Texas Rebellion began. I was photographing some “ghost signs”—I’m not sure what other people call them, but that’s how photographers and preservationists often refer to signs that were hidden and now are uncovered. Anyhow, I’m on the streets of Gonzales, and a big guy in a big pick-up truck pulls up beside me and asks me what I was photographing. I told him, “Americana.” “If you’re interested in Americana, go to Templin’s Saloon. There’s a lot of history there.” Immediately, he picked up his cell phone and called the bartender. “I’m sending over a photographer.” Hearing his tone of voice, and eyeing the rack of shotguns behind him, I followed his suggestion.

There were a lot of interesting artifacts on the walls. The young bartender gave me about a half-hour tour. When he was finished, I pointed towards a low wall in the bar, the first thing I had seen upon entering, and asked what it was. “Oh, that. My grandmother had to sit behind there until 1965. That’s a segregation wall.” He explained to me that in Gonzales, there weren’t a lot of Black people, but about half the people were Hispanic. It was common at the time to enforce segregation of white people and Hispanics, as well as Black people. I knew of segregation walls but I had never seen one in person; they were an abstract notion in my mind. Seeing the reality of it shocked me.

GF: And how did the project continue?

RF: I became more and more curious, and I spent more and more time researching locations and reading stories. I put together over the years a sort of itinerary: a Google map of hundreds of places that I wanted to visit and document. I felt like I could use my skills as a photographer to preserve evidence of these incidents and these places so that, someday, when it was all gone, people would be able to look back and see what we lived like and how we structured our environment. When I got to the point that I didn’t feel like I was doing enough, that’s when I started looking at grants. How can I actually pursue this, more wholeheartedly and more intentionally? I wanted the ability to go where the story led me, not just where I had paying work. I was encouraged to apply for a Guggenheim by a great mentor of mine, Mary Virginia Swanson, AKA “Swanee.”

My first application wasn’t powerful enough. The following year, ironically, I benefitted from two terrible tragedies: the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd. My commercial and editorial clients evaporated overnight. I ended up using the long lockdown to do research and really polish that Guggenheim application. When George Floyd was murdered, it elevated public (white) awareness and support of the Black Lives Matter movement. It became something that more white people accepted, acknowledging that racism affected much of our society.

The Guggenheim is the most prestigious acknowledgment I have ever received for work that I’m doing. The encouragement was profound validation, and the money was important: it made it possible for me to spend nine months on the road, which is what I did with my funding. I traveled the country in my Honda CR-V for nine months, driving just under 25,000 miles. It was an incredible gift, and I used it all to tell this story.

GF: I know you have a unique artistic process. Could you speak a bit about that?

RF: Well, the way I take photographs can take hours or days or weeks. At Templin Saloon, I was planted in one location for several hours. I was trying to photograph the scene in minute detail so I could composite it in a completely accurate way, but provide details that would otherwise be lost. At one moment, the television on the wall changed from some sporting event to CNN. Mitch McConnell was explaining why the senate would not move on the nomination of Merrick Garland by Barack Obama. That was another reminder to me that the issues of race are still current events. It’s not a past history. It’s not a dead history. It’s living history. The racial aspects of that obstruction are debatable, I suppose, but my opinion was that it was elemental, and so I wanted to include that detail in the final photo. All the photos contain an enormous amount of detail. When I was shooting, I wasn’t thinking about the book, I was thinking about museums that acquire my work, and the walls on which I’ve seen my work hang. I wanted to be able to create images of such detail that people would feel like they were standing next to me in the very place I was.

Growing up in Chicago, I visited the Art Institute hundreds of times. I was always influenced by the largest canvasses I’d see, like “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” by Seurat. I would sit in front of that one powerful pointillistic painting for so long. My dad took me there almost monthly, and my school field trips would frequently land right there in front of Seurat’s magnificent and inventive masterpiece. It intrigued me how this reality was made up of little dots of color.

I also loved Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” which was another treasure at the Art Institute. It was very realistic, but it subtly depicted an element of time. It was as if Hopper had just stepped out of the scene so that he could paint it. Additionally, I saw many breathtaking paintings of the American West, presented on a grand scale. The monumental size of these canvases reflected the boundlessness of the American West. The detail and luminosity of these immersive panoramas reflected the artists’ representation of the scene over time, incorporating the varied light that they witnessed.

I wanted to create a similar effect in my photographs, so I began using a technique called “stitching,” where I shoot hundreds of detail pictures, which I weave together like a single tapestry of separate threads.

David Hockney was doing this in a fabulous fashion, which influenced me. His images were impressionistically jumbled, emphasizing that these were separate images coming together to form a whole. I wanted to be less visible. I don’t want these photos to be about me; I want them to be about the place. I learned how to assemble these little pictures into a single composite that maintains the spatial relationships that I feel are critical.

These images need to be accurate and authentic because I intend them to be evidence of who and what we are. This painstaking technique also allows me to paint with light, which I couldn’t accurately achieve in a single exposure. You see that subtly the light is unusual. I take so much time making the photograph that the light changes and I exploit that where it’s beneficial.

These images need to be accurate and authentic because I intend them to be evidence of who and what we are.

GF: How does your photojournalism background inform your work?

RF: It is of paramount importance to me that what I present is factual. I know it’s impossible for me to completely negate my opinions, but I don’t want to just present my emotional response to a scene or a person or an event. Shooting in such a time-intensive manner forces me to slow down, to ponder, to look beyond my visceral responses, to really be thoughtful. I sometimes think I exercise my intellect, my mind, to the detriment of the rest of my soul. But that’s how I am. I’m curious. I like to think about things and study them and find a way to convey what I’ve learned.

GF: How did this project become a book?

RF: Well, as I mentioned, I was imagining these images as photographs on walls in museums and galleries. My desire has always been to make these prints huge. The New Orleans Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston have some immense prints of mine in their collection: almost four feet by six feet. But such grand scale requires a large amount of wall space. Few people, or even museums can dedicate that much real estate to them.

I’m hesitant to say this, because I want to be humble and I am humble, but I do think this project is socially significant and timely. I want these images to be seen by a broad swath of American society, especially children, who might learn early on of our actual history and how it is embedded all around us.

I started thinking, this should actually be a book, a portable form that can be in classrooms or be shared and discussed. When I started down that road, I also came to the conclusion that I wasn’t able to tell this story on my own.

I’m a good photographer, I’ll own that; but I don’t know a thing about being African-American or Asian or Hispanic or Native American in our nation. To do justice to this profound and pervasive story, another voice was needed, one that would be authentic and could tell the story with nuances and insights that can only be gained with experience. My voice alone could not tell this story.

GF: I’d love to know more about that collaboration.

RF: My partner in this is Dr. B. Brian Foster. He’s a remarkable writer. I find him to be both a poet and a scientist; an academic and a sociologist. He thinks about data, but he is also in touch with his personal history and his emotions. Brian had written a book called “I Don’t Like the Blues,” about the ironic relationship of the Black community in Clarksdale, Mississippi to the economic development opportunities of Clarksdale’s claim-to-fame: the blues. It is clear, in reading Brian’s book, that he, too, finds history embedded within “place.” The town is redolent with the spirits of people who passed through and those who lived in the vicinity. These are our ghosts.

I thought this guy would be a great partner. He didn’t know me at all, but he was open to looking at the work I had done. We agreed to meet in Oxford, Mississippi, where he was teaching at the University of Mississippi. While together, we took a weekend road trip to Clarksdale and checked each other out. It was great. It was one of those gifts—like Grandpa giving me a camera. Brian came into my life and he changed it. He brought a level of understanding and importance to this project that I would not have been able to do. This project needs a lot of voices, and Brian’s is beautiful.

GF: It strikes me that this chimes with what we were talking about at the beginning, with the nature of these photographs. There’s a need to be in conversation with them. And it sounds like, in Brian, you found a perfect conversation partner.

RF: I really did. The project is so much richer because of Brian’s participation. Our collaboration elevated every aspect of the book.

GF: What’s next for you?

RF: Well, that’s a great and important question that I asked myself when I got done with nine months of road tripping around the United States. I thought, I’m done with this, I never want to go back out on the road for anything again. But in the year and half since I returned home, I have come to realize just how much I’ve missed, how much I didn’t photograph: places that I knew of but couldn’t get to, or I couldn’t get permission, or the light wasn’t right, and especially the places of which I knew nothing.

Parts of my project are not in this book. I went to four or five Japanese internment camps over the course of this project. None of that is in the book. I photographed LGBTQA+ scenes of oppression, and Native American residential schools. There are mosques that were scenes of pain and suffering, the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh and other places of antisemitic actions. Our ability to define humanity by our tribal identity knows no bounds. We have “othered” so many people. I want to honor all people. We can only achieve our full potential when we recognize and honor our shared humanity, which is so much greater than our humble differences. I would like to go back on the road again and do more to nurture our connections.

And right now, with this book, I’m trying to bring into the public awareness and foster its potential. So I’m doing interviews and speaking engagements, but I’m much happier when I’m invisible and behind the camera, not in front of it.

GF: I think you’ve done a beautiful job speaking for the work.

RF: Thank you. I really could not have done it without the Guggenheim Foundation’s help: the money and more importantly, the validation, the encouragement. It makes me feel that this project is important enough to dedicate my life to it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.